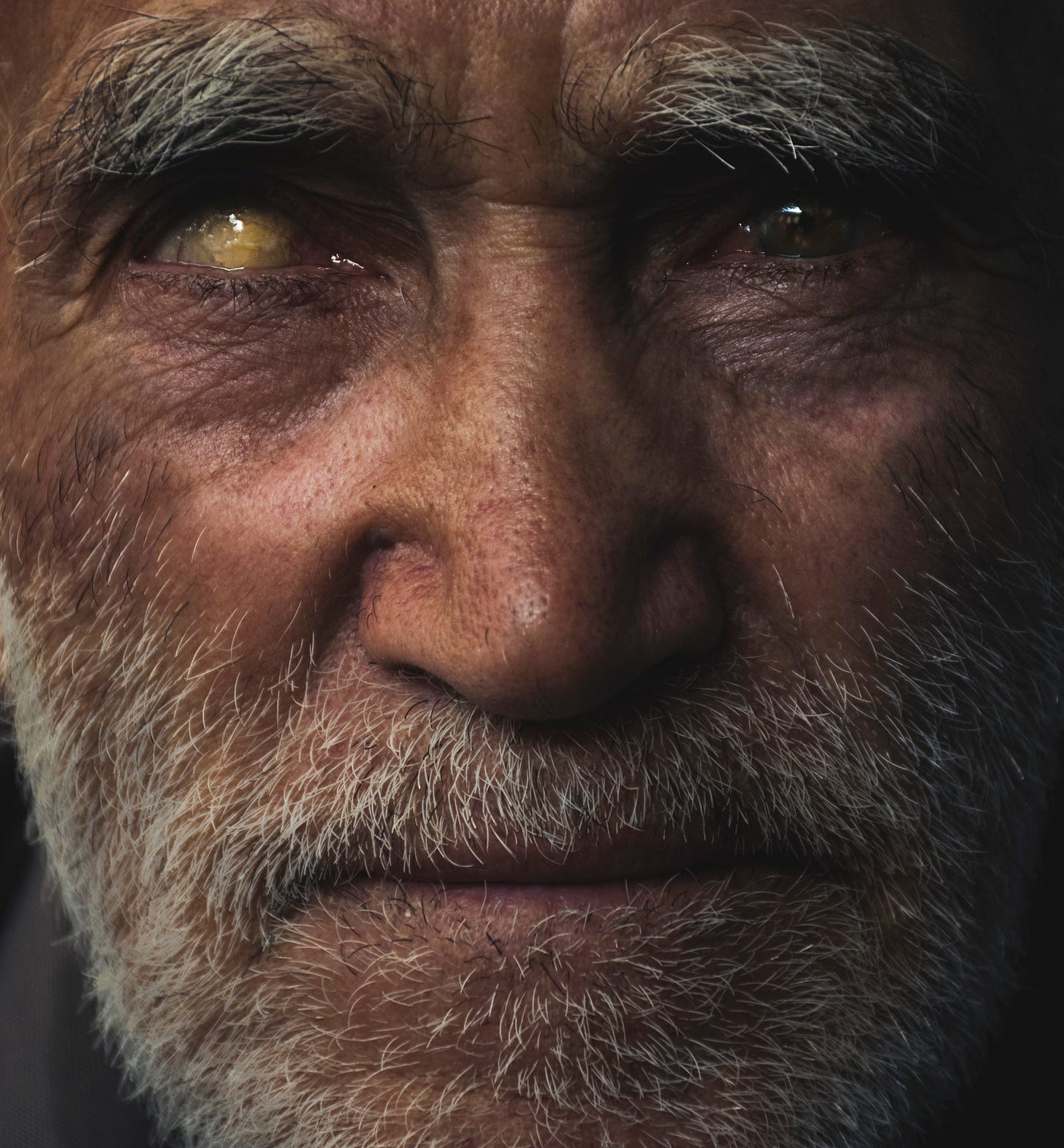

Caleb lived in the shed. “Boys live in sheds,” father always said, a scarred man with one good eye, “live in sheds until my god says when.” Father was unschooled, rigorous, and committed to the shape of his faith.

Caleb was twelve years old. Sometimes on a cool night he stuffed leaves in his pants. Mornings, he cleaned his teeth with fingers in the creek after father unlocked the chains.

Father and Caleb lived far in the mountain, got by on traps, a few crops, and an occasional trip to town. Mom left for a grave years before.

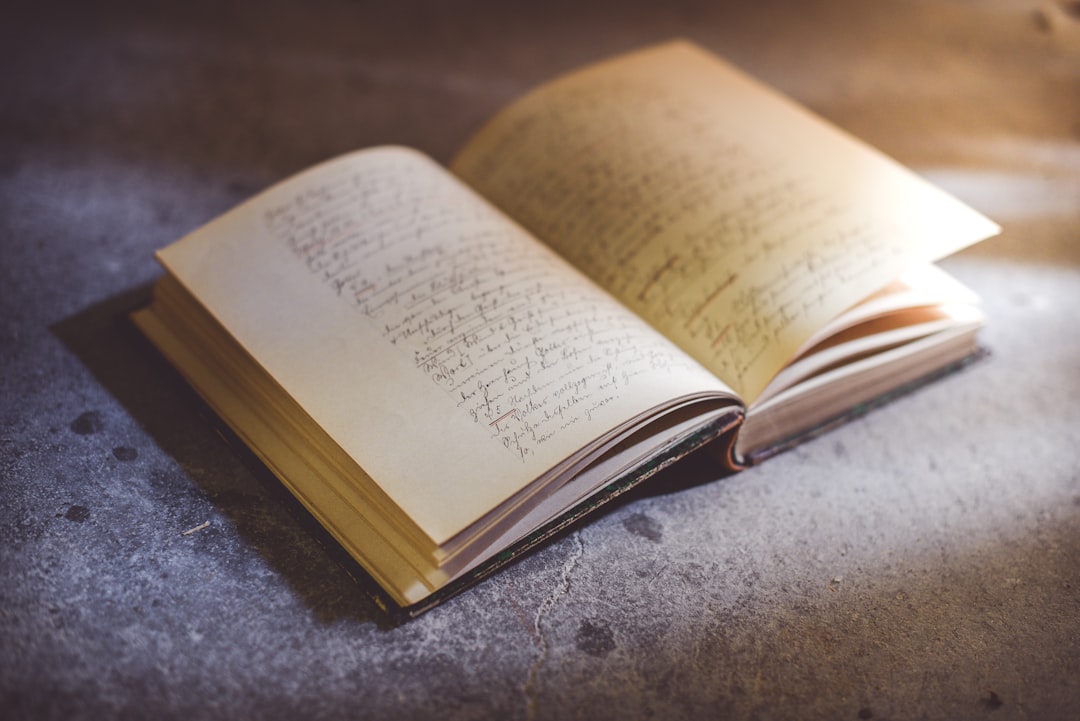

“What’ll it be today, son?” asked father. The tree shadows stretched west. “Do you want the book?” Father could follow the lines of letters slowly across the page.

“Yes sir,” said Caleb. It was forbidden to say no. He massaged his wrists, helped blood flow past bruises into his fingers.

Father nodded, pulled the book from his coat, began to read.

Once was Abraham. Killed his son with a knife, a son born of woman and blood, returned to the same. With this price, Abraham entered the kingdom.

“Why?” asked Caleb, the same question he always asked.

“Son ran from Abraham. A sin,” said father.

Caleb didn’t understand why a father would kill a son. Sin or no sin, death ought to be for the old. Maybe son concealed a demon, a monster to be chained at night lest it hurry to infect with sickness a healthy home.

A twig snapped and a young woman stepped from the trees. She carried a knife. “Take this,” she said to father who pulled back his hand. “A gift.”

“Don’t want it, who are you?” said father, a scowl dripping from his forehead into his eyes and onto his mouth.

The mountain took a breath in form of a breeze across the woman’s face; her hair rippled. She didn’t answer, turned her head, held out the knife to Caleb. “Take it,” she said.

Caleb hesitated, took it, ran his thumb over the steel edge, used his fingers to caress the handle. It felt rough, like an old Cedar tree, and as strong. He imagined himself for a moment a king among vanquished foe, smell of bloody skin, last moans and testaments, animal panting, a summer sky, flies on their feasts, the sun just lowering, the intoxication of success.

“What do I do with it?” he asked.

The woman looked at father, at Caleb, placed two fingers near her throat.

“Kill the man,” she said. “Or kill the messenger.”

It was an old expression Caleb had heard many times. And father always favored the messenger. Outside thoughts, father said, were poison. But Caleb had doubts. His wrists ached; he often dreamed he was a bird.

“This is your chance,” the woman said.

My chance, Caleb thought. “I’d like to go with you,” he said.

“You can’t leave me,” said father. “We belong to Abraham.”

“He can leave you,” said the woman. “And he will. If not today, tomorrow. Or the next. A boy must leave his father sooner or later.”

“I will find you, son.”

“But I have the knife.”

“You would kill your father?”

Caleb thought no, he would not; a father was both a pillar to hold a son aloft and a boulder to block his passage. But Caleb would walk and choose which. He longed to hear other voices, to reach others who lived on the shackled edge of freedom. Most of all, the brief vision of his kingdom lingered, and he wished for it to never fade.

Thanks for reading Dynamic Creed. If you enjoyed this piece, please tell your friends. Subscribe for free to receive wonderful new fiction from the edge of life once a week. Yours in solidarity, Victor David.

I’d love to hear what you think, good, bad, or otherwise. At the tone, please leave a comment. Beep.

This is fantastic, Victor. I'm an atheist for the most part but was raised by evangelical types who used the Bible as an intellectual bludgeon. What you evoke here about fathers and sons sometimes also pertains to mothers and daughters. Thank you for writing this.