The church stood closed for the night. Darkness hunched on the pews. It was open for business. All of these things were true.

The business passed in the backroom where angels mourned, where those who came to catalog the deaths of their dreams entered through the rear door. No money changed hands. No fists were traded.

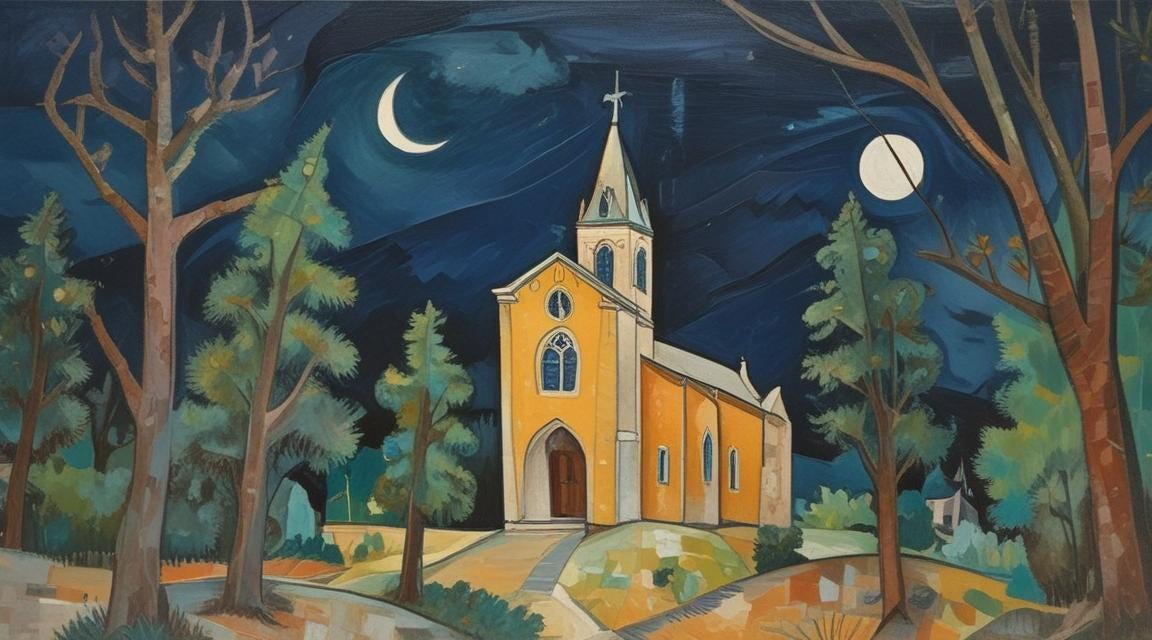

Above a roof, almost defeated by the tops of trees, a moon that once lived a full life slivered. The town, in a slight valley that looked up to the graveyards, had no breath to waste on why judgment had come, only on what to do.

Their needs are sensible, said Matthew. And the backroom pulsed small coughs of assent from the men and women gathered there.

Samuel of the hardware store tapped the table. His world was bolts and brackets that held his reason together. No they’re not, Matthew, he said.

More assent expelled itself from low throats, as if the gathering was not of one mind.

It wasn’t. Some wanted to fight.

Others, like Judith, who came softly to all encounters, preached submission. Do we want to live? she asked.

Quite the rhetorical question as rhetorical questions usually go, but in the backroom, with packs of cigarettes on the table, and stained fingers on cheeks and sleeves, it carried upon its curved back a true and brutal interrogation. Could the town survive?

The river flowed from the highlands, and was to be diverted to make a factory that would produce small metal things. There was demand, the judgment said, and a future to placate.

We went to the government meetings, said Deborah. We protested.

True. Nobody had protested more. Deborah had left an arm under a bulldozer.

Yes, said Matthew. We did what we could. And they gave us the land. They granted the town clemency.

It’s not theirs to give, said Samuel. And even so, it’s not enough. We need water.

Can we not believe in rain? It was Abigail, an old woman who lived on the edge of town. She brought goats into the world. Nobody knew her age.

It was possible, the rest agreed with nods and pursed lips. The skies wept streams upon the valley at each death of an angel, which happened frequently, as if only those who had been thrust from the cities by a pandemic of pious ignorance and had taken refuge in the knowledge of the profane could prosper.

It was possible, but not probable. A river’s whims are fewer than those of rain.

Then we fight, said Deborah.

There must be another way, said Matthew. He stood, went to a small window. With the darkness outside, he saw his face reflected, and he may have wondered when he lost his courage.

The door opened. A man with papers in his hand entered. He held them out. This is it, he said. It’s time.

Time indeed. Time to stand up, or tumble down a mound of knives into acquiesce.

They weren’t the only ones. They weren’t the first people to abandon their burial grounds and make a new start, but they were the first of their town, as all have been in their own town, in their own moment of reckoning. As such, they didn’t care about the history of forced relocation, or its motives. To them, even though theirs was an old story, it was new.

What are those, Simon? asked a man with clenched smoke on his teeth. He pointed to the papers.

Last notice, said Simon.

That’s all it took to make the backroom murmurs fade into the walls. They all knew what it meant, and where their choices could take them. Some had wanted to pretend that the day of decision would never force dawn from its bed; others had burned that notion last fire day.

Samuel stood. He threw his cigarette down, and rotated his boot heel over it, as if crushing the judgment. Matthew turned from the window; his forehead plowed a field of wrinkled acceptance. Deborah took a deep breath, clenched her remaining fist.

Choice was now narrowed, forced. The rain would come again someday, perhaps soon, a symbol of peace even, but meanwhile, they couldn’t wait. The men and women looked around at each other. Outside, the moon threw its last shard of light on the steeple.

— — —

Thanks for reading Dynamic Creed. Here’s what happened. This line:

Time flies. Time is a thief. Time heals. Two of these are true.

from Death Art by

gave me a spark that I used to start this story. As you can see, I used Jim’s phrasing to enter the sector where the judgment of water waited. My story is nothing like Jim’s, but he did indeed push the button that started the engine. The rest followed, without me knowing where it was going, which is what happens most of the time.I hope you enjoyed this piece, and please go read Death Art. You’ll be glad you did. Thanks for the spark, Jim.

— — —

As you may know, all my stories are free. However, if you’d like to consider a paid subscription, know that you’d not only be supporting me and our shared oddified sensibilities, but that I donate 25% of all earnings to animal and veteran causes.

If a paid subscription isn’t something you can do, no problem. I appreciate you all very much, and I’m doing this because I love writing these stories.

Another way you can support me is by sharing this story with others here, or with your friends and family at home. What I’d really like most of all is to connect with more people. I know that my stories don’t fit inside the designs of our time, but designs change. Spread the word, friends. The center of gravity is shifting.

Thanks again, and all the best,

Victor David

Superb writing Victor. Your story was masterfully told, and it flowed easily. I was also absolutely floored to read the Death Art mention of Jim Cummings. I had no idea. Thanks again for sharing - Jim

Beautiful, economical writing and excellent pacing!