Most said nothing when the world ended. They went to the bus stop each day at the same appointed hour and quietly summed the expected cost of their lives. They repeated the dance steps: get up, go to work, pay the rent, have a pizza. And maybe one day grab a vacation or a gun to break the circle, to overthrow the silence.

Some said things like: The milk tastes funny lately or: The music these days has no soul. They also said: Everybody says these things, and therefore gave their words no more deeper thought.

Others walked down to the government buildings when the world ended and politely asked if the president would see them because they had a few ideas to improve the average lot but the answer was always that it simply wasn’t possible without an appointment.

A few spoke the language of bombs. It was a difficult idiom that required special skills, but there were some that found mastery in the sensitive syllables of wiring, and enjoyment when a building fell or a train derailed.

Stephen Bailey had no language, only fragments. His world had already ended. Stephen went to AA meetings every week and every week said the same thing which was that he was now one day sober. He never mentioned his wife and daughter who had been on a train when a proud fierce voice in the difficult idiom of bombs bellowed.

He had tried a church when the world ended and they told him to wait until it was his turn to die when he would then be united with all that he lacked. It seemed an excuse to do nothing to Stephen. He dropped no coins in the collection box.

One day he came in his pickup truck to a stop sign and stayed there without moving or seeing while the harsh speech of horns howled behind him until one driver got out of his car and walked over to Stephen and asked if he was okay and Stephen hit the gas.

Another time he rented a room with a kitchenette and checked to see if the stove had gas that would hiss him to sleep but he hadn’t planned well and there was only a hotplate.

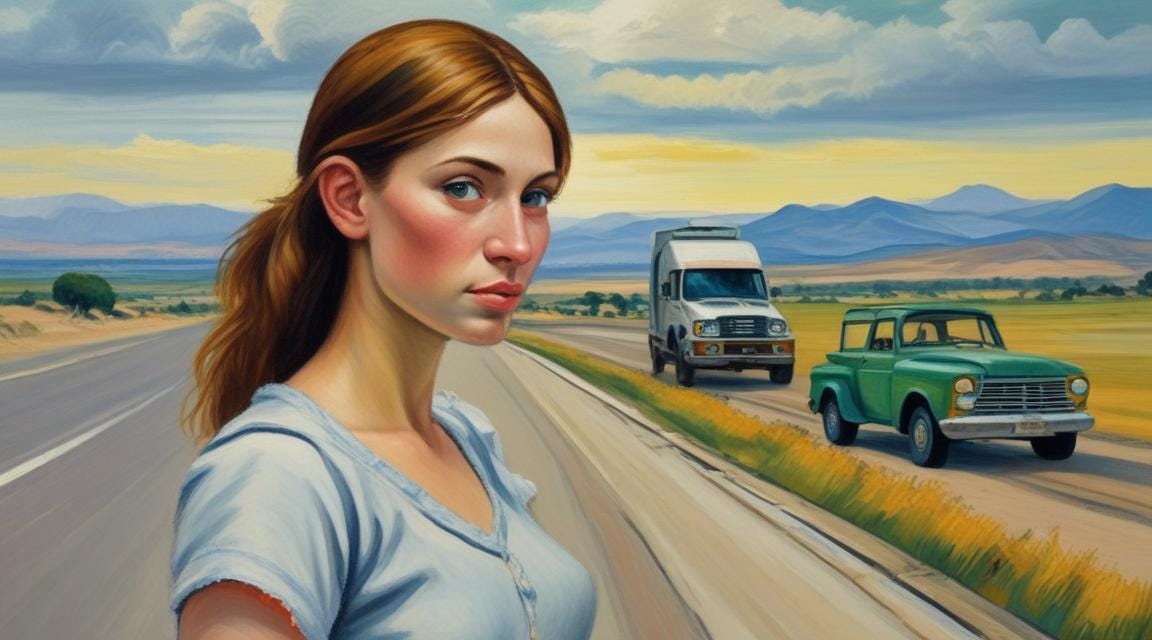

Two towns over, a girl of seventeen years who had lost her family when she could no longer hide her pregnancy stood on the road with her thumb out. Nobody stopped for fear of abetting an abortion. Their world, and their courage, had ended long ago.

Stephen had no such qualms. For him the commandments had ended too and he stopped for the girl on his way to the southern coast where he thought he might find a walk on the beach soothing. The girl climbed up and said hello and that anywhere was fine as long as it wasn’t here which was pretty much what Stephen thought also. She called herself Jane she said, as if she didn’t really believe in her own name any more, and Stephen, without explaining why, said he called himself irresponsible and culpable, although he knew that no one can predict their pain.

It was all true and at the same time false that either could have seen the future. But that’s only because in their sorrow and guilt they wandered in speculation between one thing they might have done differently and another.

Which is what a lot of people said when the world ended. They said they could have paid more attention to the rise of hateful words and the enduring unwillingness to consider empathy over disdain. The could have talked to their neighbors. They could have thrown a house party for the homeless.

Jane and Stephen shared a laugh on the way to the coast when Stephen admitted he rarely washed his socks any more because he had nobody to smell his feet. It was somewhere between a joke and a confession, but at least they found themselves for a moment lifted. At the same time the sky lightened as a cloud opened.

How much farther? asked Jane.

We’ll be there before dark.

Before the world ends for the day.

Yes, said Stephen. Before the world ends.

Odd, and maybe blasphemous, but just saying the words made Stephen consider that maybe his world hadn’t ended just yet. He asked Jane what she was going to do and she said get a job in a café until the baby insisted it must come forth and then do what she could to give it love and compassion.

Stephen replied that he thought she’d be a good mother and that he had loved a daughter for many years until the train derailed and its windows proclaimed in the language of shattered glass that his world had shattered too.

Gods were for fools Stephen told her when Jane asked if he had the faith to cope with his loss. They spoke of resurrection for some and not for others. They climbed on their crosses and invited everyone to admire the exquisite nails.

It’s not that bad, said Jane.

No, it wasn’t, and Stephen knew that. Somewhere inside, buried but not yet dead, a part of him devoid of anger still woke in the morning without a disaster to define him.

At the coast they turned east and found a beach by the mouth of a river. It was still light enough to hide the ghosts. They walked for a while along the sand and when they came to a log, they sat. Stephen asked Jane if he could touch her child and she said yes.

He got down on his knees in the sand and laid his hand gently on her stomach. From both her womb and the sea he sensed a faint echo of life.

I remember, he said.

Yes.

Stephen well recalled all those years ago when his daughter had arrived from the mysterious hand of creation into the world with her face lit in wonder and her small hands reaching for the light. He had felt her enthusiasm in his arms and knew he would never again be alone.

And now, somehow this light touch of a life in progress brought Stephen a little closer to that time, as if it were still present and hadn’t fled over the years into an empty land. It was a trick of the heart and fingers but for a moment welcome.

And for a moment, undisturbed.

The tide moved closer. The gentle swells spoke of a rebirth that had traveled a great distance. Jane lifted Stephen by his hand as she rose from the log.

Let’s go, she said. We’ll find a place to eat.

They walked back to the pickup truck. A light breeze teased the sand. The sun fell behind the water and waves lapped and gulls flew away. The world ended for a while. Nobody knew for sure, but maybe in the morning it would climb from a depth and begin anew.

— — —

Thank you for reading Dynamic Creed. Please hit the heart if you liked this piece, and most certainty drop a comment if you would. I always love to hear from you.

Victor David

All my stories are free but if you’d like to do a paid subscription, you’d not only be supporting me but helping veteran and animal causes. I donate 25% of all proceeds. Thanks for considering it, and stay blessed.

Superb writing Victor. As always, deep, meaningful and expressive. So well done. - Jim

Beautiful and powerful!